SIEVE: Cache eviction can be simple, effective, and scalable

TL;DR Caching bolsters the performance of virtually every computer system today by speeding up data access and reducing data movement. By storing frequently accessed objects on a small but comparatively fast storage device, future requests for that cached data can be processed rapidly. When the capacity of a cache is much smaller than the complete dataset, choosing what objects to store in the cache, and which to evict, becomes an important, hard, and fascinating problem.

Here, we present a new cache eviction algorithm called SIEVE that is simpler than the state-of-the-art algorithms while achieving superior efficiency and thread scalability.

Caching and eviction algorithms

Caching is a vital tool for optimizing the performance of slow backends. A good cache should (1) serve as many requests as possible from the cache, and (2) serve as many requests as possible in a time interval. The former is often measured by miss ratio — the fraction of requests that cannot be served from the cache; while the latter is often measured by throughput — the number of requests the cache can serve per second.

When the cache fills up, writing new data requires discarding some old data. The algorithm that decides which data to evict is called a cache eviction algorithm. Least-recently-used (LRU) is the most common eviction algorithm used in production systems. An LRU implementation often uses a doubly linked list to maintain the last-access ordering between objects. Upon each cache read, the requested object is moved to the head of the list. To insert an object when the cache is full, the object at the tail of the list is evicted. LRU is simple and effective because data access often exhibits temporal locality — recently accessed data are more likely to be accessed again soon.

While it is the most common eviction algorithm, LRU leaves a lot of efficiency on the table compared to an offline optimal caching algorithm]. Over the past sixty years, many new cache eviction methods have been designed with the goal of achieving a lower miss ratio. Many of these algorithms descend from LRU — often using one or more LRU lists. For example, ARC[^1] internally employs four LRU lists, two of which store recently and frequently accessed data, and two of which track recently evicted data.

Figure 1. Eviction algorithms have become increasingly complex over time. The darkness of color indicates the complexity of the algorithm.

While a range of algorithms have been proposed to improve efficiency, they have become increasingly complex over time. As a result, these algorithms are difficult for systems builders to implement and debug, and most of them have never been adopted in real systems.

Moreover, LRU and LRU-based algorithms suffer from a scalability problem. Because each cache read modifies the head of a doubly linked list, which is guarded by a lock, an LRU cache cannot exploit the many cores in modern CPUs.

Can we yearn, then, for a cache algorithm that is not just efficient and scalable, but also simple enough to be practical? History suggests the pursuit is unlikely to bear fruit, but a richer trove of data than researchers have previously had available lends us hope.

Modern web cache workloads

While the very mention of caching may conjure images of traditional block and page caches, the web cache deployments that power our online life have grown meteorically over the past decade. In the data center, for instance, key-value caches are widely deployed at scale (e.g., PBs at Google[^2]) to temporarily store computed results, such as SQL query results and machine learning predictions. On the edge of the Internet, Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) deliver images and videos to end-users quickly and cheaply.

The data access patterns of these web caches, specifically in key-value and CDN workloads, differ markedly from traditional page cache workloads. For instance, whereas loops and scans of address ranges are common access patterns in block cache workloads[^3], they are very rare in web cache workloads. Instead, the objects in web cache workloads invariably exhibit skewed and long-tailed popularity distributions that follow a power-law[^4].

Figure 2. A toy example illustrating that shorter request sequences have higher one-hit-wonder ratios. There are seventeen requests for five objects, one of which (E) is a one-hit wonder. In a shorter request sequence, e.g., from the first to the eighth request, there are four objects, two of which (C and D) are one-hit wonders.

Our recent study found that most objects in web cache workloads are never reused before being evicted[^5]. Following an industry convention, we call these objects one-hit wonders. The metric one-hit-wonder ratio measures the fraction of objects being one-hit wonders in a request sequence. We found that shorter request sequences often show higher one-hit-wonder ratios. The figure above shows an example request sequence, where the full sequence has seventeen requests for five objects. There is only one one-hit wonder in the sequence and the one-hit-wonder ratio is 20%. However, if we consider only the window of requests between one and eight then there are four objects being requested and the one-hit-wonder ratio is 50%.

Why do we care about short request sequences? The reason is simple — a cache has limited capacity, so it will not observe the full request sequence before it begins to evict objects. The implication of this observation is that most of the objects in the cache are not reused before eviction. Therefore, we should not keep these objects around in the cache for a long time. But how do we know what items are worth keeping?

How to design more efficient yet simple eviction algorithms

We view a cache as a list logically ordered by eviction preference — items would be evicted in that preference order[^6]. Promotion and demotion are two internal operations used to maintain the object ordering in a cache. Traditional LRU-based algorithms use eager promotion, which moves an object to the head of the list upon each request. Meanwhile, they rely on passive demotion to move objects down the list.

However, the LRU approach has two drawbacks. First, eager promotion requires taking a lock on each cache hit, which limits the throughput and scalability of the cache. Second, as we have shown, many objects in the cache are one-hit wonders, yet passive demotion allows them to stay in the cache for a long time and waste precious space from others. The problem gets amplified in the big data era where a huge volume of data is being generated while most data are rarely accessed again.

Figure 3. Traditional LRU-based eviction algorithms focus on eager promotion and passive demotion. We argue that quick demotion and lazy promotion should be used.

We argue that an efficient cache eviction algorithm should use lazy promotion and quick demotion[^6]. Lazy promotion decides whether to promote cached objects or not only at eviction time, aiming to retain popular objects with minimal effort. An example of lazy promotion is adding reinsertion to FIFO (First-in-first-out). Lazy promotion can improve (1) throughput due to less computation and lock contention and (2) efficiency due to more information about an object at eviction. Quick demotion removes most objects quickly after they are inserted. This is critical because most objects are not reused before eviction. Our previous work leverages this idea and designed S3-FIFO, a cache eviction algorithm that only uses FIFO[^5]. S3-FIFO is an efficient cache algorithm that scales better than state-of-the-art eviction algorithms, but, while simple, is still more intricate than the litmus test of algorithms like LRU. Below, we introduce SIEVE, the simplest approach we have found to effectively achieve both lazy promotion and quick demotion for cache replacement.

A new cache eviction algorithm: SIEVE

SIEVE Design

Data structure. SIEVE requires only one FIFO list and one pointer called a “hand”. The list maintains the insertion order between objects. Each object in the list uses one bit to track the visited status. The hand points to the next eviction candidate in the cache and moves from the tail to the head of the list. Note that unlike some existing algorithms, e.g., LRU, FIFO, and CLOCK, in which the eviction candidate is always the tail object, the eviction candidate in SIEVE is an object that can be in the middle of the list.

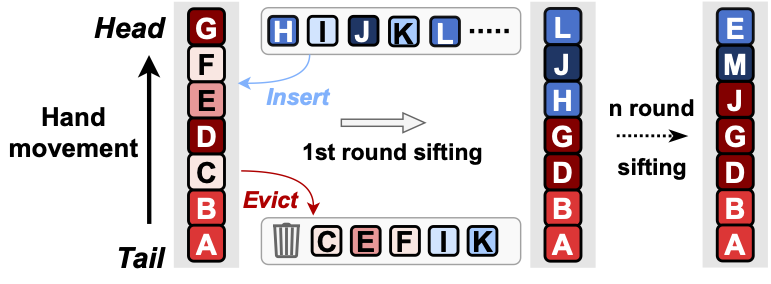

Figure 4. An illustration of SIEVE operations.

SIEVE operations. A cache hit in SIEVE sets the visited bit of the accessed object to true. For a popular object whose visited bit is already set, cache hits do not perform any metadata update. During a cache miss, SIEVE examines the object pointed by the hand. If it has been visited, the visited bit is reset, and the hand moves to the next position (the retained object stays in the original position of the list). It continues this process until it encounters an object that has not been visited, and it evicts the object. After the eviction, the hand points to the previous object in the list. While an evicted object is in the middle of the queue most of the time, a new object is always inserted into the head of the queue. In other words, the new objects and the retained objects are not mixed together. We illustrate SIEVE operations above.

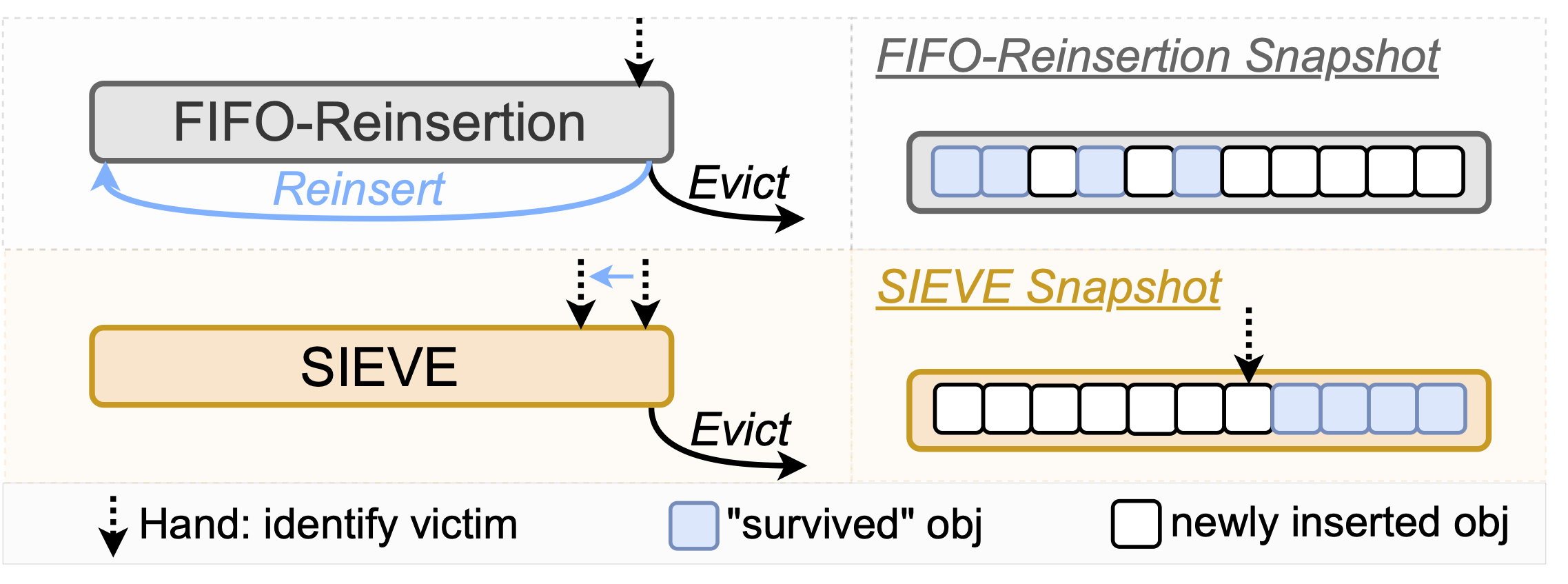

Figure 5. A comparison of SIEVE and FIFO-Reinsertion.The left shows the insertion strategy, while the right shows the difference between object ages between FIFO-reinsertion and SIEVE. Both algorithms use one bit to track object popularity. However, FIFO-Reinsertion reinserts retained objects to the head, mixing with new objects, while SIEVE keeps retained objects at the original position, separating old and new objects.

At a glance, SIEVE looks similar to FIFO-Reinsertion, also known as CLOCK and Second Chance, which also uses a bit to track popularity. However, SIEVE differs in where a retained object is kept. SIEVE keeps the object in the original, old position. FIFO-Reinsertion, in contrast, inserts the object at the head, together with newly inserted objects, as depicted in the figure above. The moving hand permits SIEVE to perform quick demotions. When the hand moves to the head, new objects that have not been revisited are quickly evicted. We describe the algorithm in more detail below.

def cache_hit(obj):

obj.visited = true

def next_hand(hand):

hand = hand.prev

if hand is None:

hand = tail

return hand

def cache_evict():

# find the first object that has not been visited

while hand.visited:

hand.visited = false

hand = next_hand(hand)

obj_to_evict = hand

hand = next_hand(hand)

# evict the object

obj_to_evict.prev.next = obj_to_evict.next

obj_to_evict.next.prev = obj_to_evict.prev

remove_from_hash_table(obj_to_evict)

Evaluation

| trace collection | collection time | #traces | cache type | # request (million) | # object (million) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDN1 | 2021 | 1273 | object | 37,460 | 2,652 |

| CDN2 | 2018 | 219 | object | 3,728 | 298 |

| Tencent Photo | 2018 | 2 | object | 5,650 | 1,038 |

| Wiki CDN | 2019 | 3 | object | 2,863 | 56 |

| Twitter KV | 2020 | 54 | KV | 195,441 | 10,560 |

| Meta KV | 2022 | 5 | KV | 1,644 | 82 |

| Meta CDN | 2023 | 3 | object | 231 | 76 |

You may wonder how much better a simple algorithm like SIEVE can outperform LRU. We used open-source traces from Twitter, Meta, Wikimedia, Tencent, and two proprietary CDN datasets to evaluate the algorithms. We list the dataset information in Table 1. It consists of 1559 traces that together contain 247,017 million requests to 14,852 million objects. We implemented SIEVE and state-of-the-art eviction algorithms in libCacheSim[^7] to compare their efficiency. We have also implemented SIEVE in Meta Cachelib to compare its throughput and scalability with optimized LRU. We replayed the traces as a closed system with instant on-demand fill.

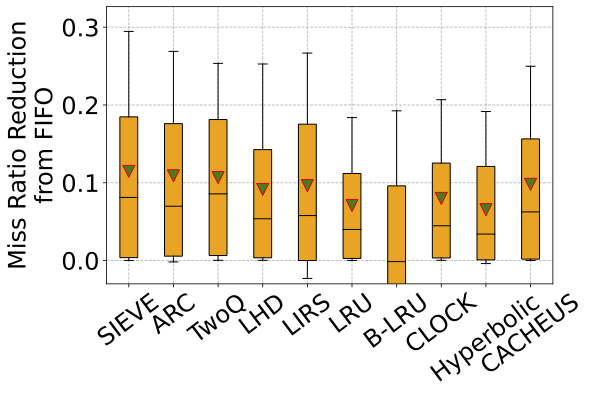

Miss ratio serves as a key performance indicator when evaluating the efficiency of a cache system. However, when analyzing different traces (even within the same dataset), the miss ratios can vary significantly, making direct comparisons and visualizations infeasible. Therefore, we calculate the miss ratio reduction relative to FIFO.

Figure 6. The boxplot shows the miss ratio reduction from FIFO over all traces in the CDN1 dataset. The box shows P25 and P75, the whiskers show P10 and P90, and the triangle shows the mean. SIEVE achieves similar or better miss ratio reduction compared to state-of-the-art algorithms.

Efficiency. Figure 6 above shows the miss ratio reduction (from FIFO) of different algorithms across traces. SIEVE demonstrates the most significant reductions across nearly all percentiles. For example, SIEVE reduces FIFO’s miss ratio by more than 42% on 10% of the traces (top whisker) with a mean of 21%. As a comparison, all other algorithms have similar or smaller reductions on this dataset. For example, CLOCK/FIFO-Reinsertion, which is conceptually similar to SIEVE, can only reduce FIFO’s miss ratio by 15% on average. Compared to advanced algorithms, e.g., ARC, SIEVE reduces ARC miss ratio by up to 63.2% with a mean of 1.5%. Note that, more than 1000 traces were used in the evaluation, so a small move of the box (e.g., the mean value) is non-trivial. We refer interested readers to further figures in our NSDI’24 paper[^8].

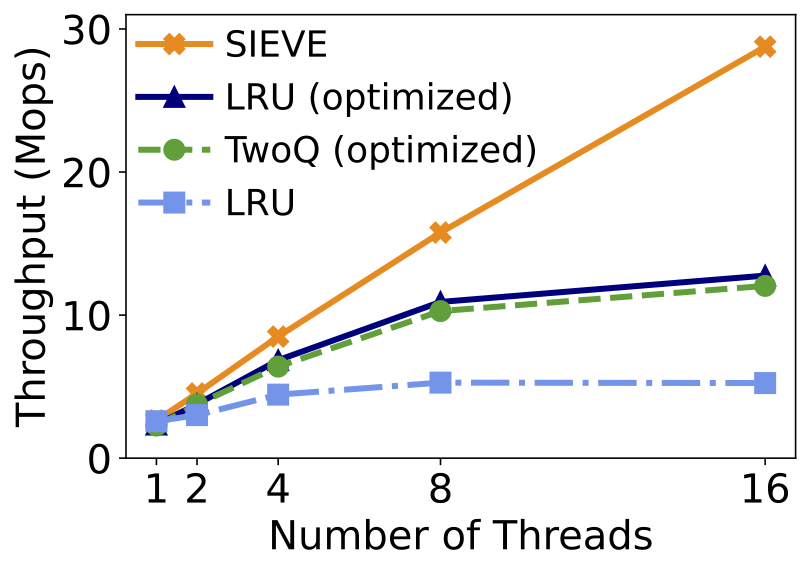

Figure 7. SIEVE achieves better thread scalability than optimized LRU.

Scalability. Besides efficiency, throughput is the other important metric for caching systems. Figure 6 BELOW shows how throughput grows with the number of trace replay threads using a production trace from Meta. Because scalability is important for production systems, Meta engineers spent a significant amount of effort to improve the scalability of LRU-based algorithms. For example, objects that were promoted to the head of the queue in the last 60 seconds are not promoted again. Moreover, Cachelib uses a lock combining technique to elide expensive coherence and synchronization operations to boost throughput. Therefore, the optimized LRU and TwoQ show impressive scalability results compared to strict LRU. Compared to these LRU-based algorithms, SIEVE does not require “promotion” at each cache hit. Therefore, it is faster and more scalable. At a single thread, SIEVE is 16% faster than the optimized LRU. At 16 threads, SIEVE shows more than 2× higher throughput than the optimized LRU and TwoQ on the Meta trace.

| Cache library | Language | Lines of change |

|---|---|---|

| groupcache | Golang | 21 |

| mnemonist | Javascript | 12 |

| lru-rs | Rust | 16 |

| lru-dict | Python + C | 21 |

Simplicity. SIEVE not only achieves better efficiency, higher throughput, and better scalability, but it is also very simple. We chose the most popular cache libraries/systems from five different languages: C++, Go, JavaScript, Python, and Rust, and replaced the LRU with SIEVE. Although different libraries/systems have different implementations of LRU, e.g., most use doubly-linked lists, and some use arrays, we find that switching from LRU to SIEVE is very easy. Table 2 shows the number of lines (not including the tests) needed to replace LRU — all implementations require no more than 21 lines of code changes.

Why does SIEVE work?

Figure 8. An illustration of why SIEVE works. The density of colors indicates inherent object popularity (blue: newly inserted objects; red: old objects in each round), and the letters represent object IDs. The first queue captures the state at the start of the first round, and the second queue captures the state at the end of the first round.

You may wonder why this algorithm is called SIEVE. The reason is that the “hand” in SIEVE functions as a sieve: it sifts through the cache to filter out unpopular objects and retain the popular ones. We illustrate this process in the figure above. Each column represents a snapshot of the cached objects over time from left to right. As the hand moves from the tail (the oldest object) to the head (the newest object), objects that have not been visited are evicted. For example, after the first round of sifting, objects at least as popular as A remain in the cache while others are evicted. The newly admitted objects are placed at the head of the queue. During the subsequent rounds of sifting, if objects that survived previous rounds remain popular, they will stay in the cache. In such a case, since most old objects are not evicted, the eviction hand quickly moves past the old popular objects to the queue positions close to the head. This allows newly inserted objects to be quickly assessed and evicted, putting greater eviction pressure on unpopular items (such as “one-hit wonders”) than LRU-based eviction algorithms.

Conclusion

In this article, we discuss the skewed access pattern in web cache workloads and how to design new cache eviction algorithms. We illustrate two properties that efficient cache eviction algorithms usually have: lazy promotion and quick demotion. SIEVE is a new cache eviction algorithm that leverages these two ideas, while maintaining simplicity and scalability. It uses a FIFO queue with a moving hand to retain popular objects in place and remove unpopular objects quickly.

Reference

[^1] Megiddo, Nimrod, and Dharmendra S. Modha. “{ARC}: A {Self-Tuning}, low overhead replacement cache.” 2nd USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST 03). 2003.

[^2] Singhvi, Arjun, et al. “Cliquemap: Productionizing a rma-based distributed caching system.” Proceedings of the 2021 ACM SIGCOMM 2021 Conference. 2021.

[^3] Rodriguez, Liana V., et al. “Learning cache replacement with {CACHEUS}.” 19th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST 21). 2021.

[^4] Yang, Juncheng,et al. “A large-scale analysis of hundreds of in-memory cache clusters at Twitter.” 14th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 20). 2020.

[^5] Yang, Juncheng, et al. “FIFO queues are all you need for cache eviction.” Proceedings of the 29th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles. 2023.

[^6] Yang, Juncheng, et al. “FIFO can be Better than LRU: the Power of Lazy Promotion and Quick Demotion.” Proceedings of the 19th Workshop on Hot Topics in Operating Systems. 2023.

[^7] https://libcachesim.com

[^8] Zhang, Yazhuo, et al. “Sieve is simpler than lru: an efficient turn-key eviction algorithm for web caches.” 21st USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 24). USENIX Association. 2024.

More information can be found in our website and NSDI paper.